Village History

Arthur Beckett's Memories

I was born on the 5th of April 1924 and, have lived in Culham all my life.

The village used to be quite different when I grew up. My first memory was when I started school at the age of 3. We had mattresses in the main school room. Mrs. Hughes, the school mistress, lived in the school house. There were just two classrooms. Mrs. Butterfield taught the Infants and Mrs. Hughes taught the Seniors.

I went to Culham School until I was 11 years old. I fondly remember my time at Culham School. When we progressed to the Senior Class we sometimes helped out. If the Junior teacher did not turn up for some reason, we took it in turn to take over a class. Happy Days! At the age of 11 we had to march up to Culham College Practice School. When the Abbey School was built in Dorchester, we had to transfer to that school in the Abbey Grounds. I left school when I was 14 years old.

During the school holidays the children helped in the fields leading the horses, picking up sheaves of corn or doing other chores. Whatever was necessary. They received 2 shillings and sixpence a day.

In the winter, we skated on the frozen water in the meadows.

At that time there were just 39 cottages in the village. They all belonged to the Morrell's Brewery and everyone paid rent. The Morrell family looked after their tenants and everyone received a supply of coal for the winter which was delivered to every cottage and dumped by the front gate and it had to be cleared away within 2 days. As a Christmas gift every family also received 1 blanket one year and the next a pair of sheets.

The village had 5 working farms, 2 pubs plus the one at the station.

We also had a thriving shop (General Store) with a Post Office section in the village, situated on the corner of the Green. To the side of it was the Bakery which made all the village bread and cakes. Everyone knew everyone else in the village.

When I first left school I had a handcart and delivered the bread and cakes throughout the village.

On Sunday mornings almost everyone, especially the children, went to Church. I took turns pumping the organ. The church was very warm in the winter as we had underfloor heating. I don`t know how it worked. I remember the warm air coming up through the floor gratings. I always sat next to Fred Mitchell, ex-school master of the school, next to the organ. The fire was stoked by the verger and the coal shed was on the left hand side in a little recess of the church. The old chimney still exists.

On the corner of Tollgate Road and the High Street were two cottages and between these and the School we had a very nice Hall which belonged to the British Legion. It was built of timber and quite large. A few steps led up to it. It had many windows overlooking the school playing field. It had a kitchen and toilets. The Hall was used for all social occasions including wedding receptions.

During the first year of the war I belonged to the Local Defence Volunteers, later called Home Guard, and we often used to sleep in the Hall when off duty. I can still remember the old Legion members, including my dad, wearing all their medals and displaying the Culham British Legion Flag, marching from the Hall down to the Church where the bugler was waiting for them on Remembrance Day between the war years.

We also had a full size Football Pitch in the Glebe field and a team of players to be proud of. They all looked very smart in their blue and white striped football outfits, winning no end of cups. You reached the football field from the Main Road into Abingdon next to the entrance to the Vicarage. There was also a footpath from the village to the Vicarage next to Home Farm. The Council Estate had not been built then.

All that existed then on that side of the village were the 2 cottages, the British Legion Hall, the School and School House, Home Farm, the Vicarage and Culham House.

On the river side was the Tollgate and Brick Kiln where my Dad worked until its closure. I spent a lot of time down there watching the bricks being made and put into the ovens to bake. I still remember the ponies pulling the trucks of clay up the rail line from the clay pit at the bottom to the work sheds.

There were 9 houses on the left hand side of the High Street, then a big gap. We used to come out of school and enjoy playing there. After the next 2 houses was a Bowling Green which was later built on with a house and bungalows.

Living conditions:

All the cottages were quite small. All the water had to be drawn up from a well. In our case the well served 5 houses and we had to fetch the water in buckets. The only lighting was by paraffin lamps and candles. All the cooking was done on a coal fitted range next to which was a brick built copper containing a furnace pan with a fire box underneath for heating the water on laundry days. This was attached to the same chimney as the range. Filling this and the washing trays took a lot of trips to the well with buckets, not to mention the laying and lighting of the fire.

Toilet facilities consisted of a brick building at the end of the garden containing an earth closet pail which was emptied into holes in the garden usually on a moonlit night. Apart from all this we got used to hearing the lovely sound of the church bells and the ringing was sadly missed. These conditions still existed in 1950 when I married my dear wife Jean.

The first thing to come to the village was electricity. This made a difference as the Estate put on electric pumps at the farm and a small bore water pipe through the village with about half a dozen stand pipes We all paid a small charge of £2.00 each year. We could now fetch the water from the stand pipe which was twice the distance of the well. When the electricity was off , which happened quite often, you had to go back to the well. Still, we did have some electric lights downstairs when it was on.

When the village fete was held in the Manor grounds my father used to bring a pony from the Kiln and give children rides around the field at the back of the Manor. One moment of glory came when he had his photo in the Newspaper doing just that.

It was some years later when the Mains Water came into the village and even longer for the main drainage. We had invested in a Septic Tank in the garden to bring the toilet facilities up to date, which were not needed after a good few years. Still it was worth it, even the expense. After being away for 5 years on active service in the army during the war years it was a lovely village to come home to - even then it had changed almost beyond recognition. I certainly miss all the lovely elm trees which made it such a lovely scenic village.

My Childhood in Culham

Compiled by Janet Brandon, 2011.

I have been researching the Mouldey family for about 30 years, prompted at first by wanting to know more about our rare and unusual surname. My father, Rowland Frank Mouldey, was born in 1911, so 14th November 2011 would have been his 100th birthday. Before he died in 2003 he wrote down his memories of his childhood in Culham village - a place he loved, but a place he was sent away from. His memories were jotted down on many pieces of paper, and he passed them to me. As a tribute in his centenary year I decided to write his story of his childhood, using his own words and descriptions. I hope he would approve.

The Mouldey family came to Culham about 1865, when my great-grandfather Isaac Mouldey (1804-1886) with his sons William, George and Job took over Culham Brickworks. (He had 2 older sons, but Joseph had died of TB aged 24 in 1853, and Isaac emigrated to Canada in 1858) All the family were brickmakers.

Isaac and his wife Catherine rented Kiln Cottage. The Brickworks provided a good living for Isaac, and for his sons and their families who all lived in the village. Kiln Cottage was rented from the Morrell family (Brewers in Abingdon) who owned many properties in Culham and the surrounding area as well as the Brewery. Kiln Cottage and the Brickworks were "a package". Coal for the Brick Kiln was brought in by barges.

After Isaac died in 1886 his sons continued to run the Brickworks, but Job emigrated to Canada in 1887 with his large family, and George died in 1891.

Thus, my grandfather William Mouldey became the sole proprietor of Culham Brickworks. He lived at Kiln Cottage with his wife Ellen, and their children: Edith (b 1868) William (1869) Louisa (1871) Frederick (1874) Heber(1877) Rowland (1879) Mark (1883) and Clara (1885).

William prospered at Kiln Cottage where he dealt with the administrative work of the Brickworks. He had a large safe in the hallway of the cottage. He also rented some agricultural land from the Phillips family (who lived in the big house near the Church) - this land was opposite the houses in Culham High Street, behind a high brick wall. He had a plough, and he also had a horse and cart with "Mouldey & Sons" painted on the side. Everyone knew that Grandfather liked to visit the "Wagon & Horses" and when he came out of the pub and climbed into his cart the horse knew the way home!

Grandfather had supplied the bricks for 4 houses in St John's Road Abingdon but the builder was unable to sell the houses or pay for the bricks. William took the houses in lieu of payment. His children inherited these houses, and Frederick's son (also Fred) lived in one of the houses until his death. The other houses were eventually sold.

Grandfather William's 5 sons all joined him at the Brickworks, but Heber died aged 24 and William died aged 39, both of TB. Frederick, Mark and my father Rowland remained at the Brickworks.

My parents married in 1909 and set up home in a cottage in the High Street. I was born there in 1911, 2 years after my sister Doris. I never knew my Grandfather William because he died in 1909. The Brickworks employed several men and produced up to 1000 bricks a day. The bricks were gault clay (grey) and the water's edge was white with brick dust. Bricks were first made by hand - wooden boxes filled with the clay, the top flattened off, and then the brick was tipped out and left to dry, then baked. Later they were made in slabs which were cut with wires drawn through the slab, producing more bricks at a time. Yellow bricks were made by mixing cinder with the clay, and were very strong.

Our Cottage

Our cottage was the second one in the High Street. When my Uncle Fred married he moved into the first cottage, so they were all very close to Kiln Cottage where Uncle Mark and his unmarried sister Louisa still lived.

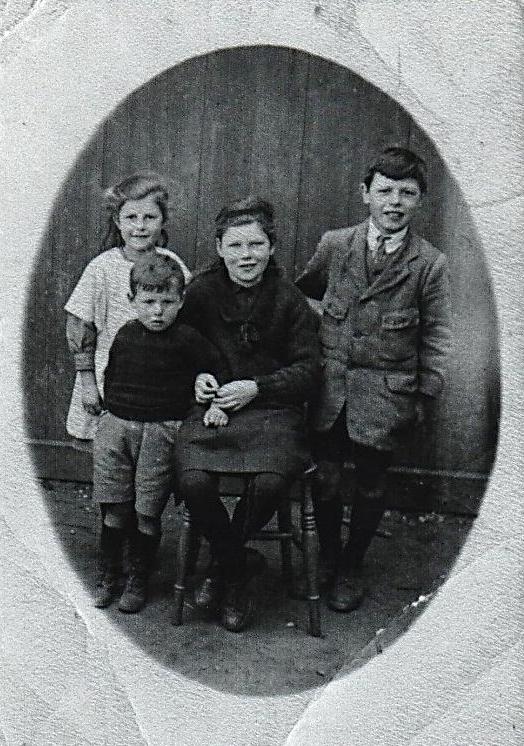

1912 - Doris & Rowland with our Mother:

Our cottage had one room downstairs that was divided into 2 rooms by a wooden partition wall that my father built. Thus we had a small "best room". The kitchen had a floor made from ordinary red house bricks and was very worn and uneven. I remember that it was difficult to get the wooden table to stand straight without a wobble!

Cooking was done on the fire in the kitchen - the saucepan or kettle placed on a trivit over the fire. I seem to remember an oven next to the fire. We had no electricity so lighting was by candles, although we did have just one oil lamp. Cold and dark wintry evenings usually meant "early nights".

We had no running water. There was a pathway at the back of the cottages. A water pump outside the first cottage served 3 cottages. My mother was worried that the water was not safe to drink and would send me with a jug to get fresh water from the spring at Kiln Cottage. I remember a shed built just outside the back of our cottage where a copper was installed. There was a bricked area under it where a fire was lit to give us hot water. The toilet was at the end of the garden. The stairs went up from the kitchen to 2 bedrooms, one for my parents and one for us children. My sister Freda was born there when I was 3, so it was quite crowded.

I don't remember any food shortages at that time because at Kiln Cottage Uncle Mark and Aunt Louisa had a cow to provide milk and butter - I remember watching Aunt Louisa making the butter and skimming milk for sale at a half-penny a jug. They also had chickens and ducks. Kiln Cottage had its own water pump, and a fresh spring. Also, the family still had the rented land for our vegetables.

I remember one incident when the plough (kept at the side of Kiln Cottage) had its wheels stolen! The local policeman came to the village school to investigate and it was found that 2 little boys had stolen them to make their own cart! They were made to replace them on our plough and no further action was taken.

We still had the horse and trap. Uncle Fred used it on Saturdays to visit his in-laws in Abingdon, and my father used it on Sundays - I remember being taken on drives to Clifton Hampden.

Going to School

I went to the village school when I was 3 years old. My mother would see us to the gate and then Doris and I walked across the road to the school on our own. The Schoolmaster was Mr Mitchell, and there was also a lady teacher in the school, but children were taught in mixed age groups, staying at the school from 3 until they finished their education. But in the early 1920s the system changed. Until then Culham College was a paying-school - not for the poorer village boys! Then our Schoolmaster retired and it was decided that boys would transfer to Culham College at the age of 11. So off I went! It was a long walk to school, especially in the Winter. At that time Culham College trained students to become Schoolteachers, so the teaching was quite good and I did well. Later on the girls also changed school at 11, being taken each day to Dorchester.

At the village school the Schoolmaster, Mr Mitchell, had lived in the Schoolhouse next door with his invalid wife. When his wife needed him she would knock on the wall and he would go next door, often being gone for hours! For several years he employed my mother's sister, Amy Powell, as his housekeeper, but then she had to return to London to look after her elderly parents. I do remember the Schoolmaster's garden! Any boy who misbehaved in class had to work in Mr Mitchell's garden after school. It always seemed to us that when there was work to be done in his garden we always seemed to be doing something wrong in class!

The Church

The Church was an important part of our lives. We were expected to go to Church on a Sunday and to go to Sunday School. When it was time for my Confirmation I remember a cartload of us being taken to Clifton Hampden Church for the service conducted by the Bishop. I remember that one Sunday the Bishop came to Culham Church to consecrate the land for the extension to the graveyard, and we all attended the ceremony.

The First World War

When WW1 started Uncle Fred joined up. My father was 35 years old, and was sent to work at a large loading bay/warehouse for munitions on the railway between Didcot and Milton. The brickworks could not continue because it could not get the coal it needed.

Fred's wife went back to live with her family in Abingdon, and around 1915 Mrs Morrell decided that she wanted Kiln Cottage for her retired gamekeeper, Mr Knowles, and the Mouldey family were given notice. Uncle Mark got married and moved to Number One High Street, next door to us. He later enlisted into the Army.

In 1917 my mother had twins - Basil and Constance. Sadly Constance died when she was a few months old. She had never been able to feed properly and my mother spent many hours trying so hard to save her. She was buried in Culham Churchyard - close to Grandfather William's grave, near the boundary hedge. My father made a wooden cross to mark her grave, but this has long gone.

After the War

When the War ended our lives had changed. Uncle Fred came home but his health was ruined by the war. He had caught TB and was never able to work manually again. He lived in Abingdon at the house in St Johns Road which he had inherited, but he died in 1921.

My father, who had enlisted at the end of the War, caught pleurisy and was in hospital for several months. At the end of the war there was a dreadful flu epidemic. I remember that I caught the flu and was ill in bed for a long time.

1920 - Freda, Basil, Doris & Rowland:

Around this time Mrs Morrell gave us a larger cottage - then Number 12 - to accommodate our larger family. The rent was about 6/- a week. At Number 12 we had our own water pump so water could be piped upstairs to a tank on the landing which fed a copper under the stairs, so now we had a bathroom with water from the copper, although we had to share the bath water. The water supply was improved. An artesian well was installed near the pub. Later a water main was laid through the village and house owners could pay to have running water in their homes.

But life was much harder for us now. There was not enough money to provide sufficient food for our growing family, and I know my parents struggled to provide for us all. My father grew lots of vegetables in the garden. I remember that I planted an apple pip in a jam jar and it grew really well! My father planted it in our front garden and so we had a lovely apple tree. When I visited Culham a few years ago the tree was still there.

The Brickworks was re-opened by Cox Bros from Abingdon and my father worked for them for a while. Uncle Mark had his own gravel pit in Abingdon.

I remember the end of the war. We had a Victory Party in the village - but it poured with rain which rather spoilt it for us children!

I remember the Tollgate between Sutton Courtenay and Culham. The Tollgate Keeper was Mr Miles, a gentleman who only had one leg following an accident of some sort before he came to Culham. The charge for vehicles was about 3d and for walkers it was a half-penny. But walkers would leave the road and walk across the fields round by the weir to avoid paying. When they decided to scrap the Toll the dignitaries from both villages met at the tollgate, and shook hands. The gate was then thrown into the water!

I remember the War Memorial at Sutton Courtenay being unveiled by Mr Asquith. I was about 8 years old and my father took me to watch. He lifted me up and put me on his shoulders so I had a really good view. When Mr Asquith (by then Lord Oxford) died he was buried in Sutton Courtenay Churchyard.

There were shops overlooking the village green and after the bread was baked the baker would put villagers' meals into his oven to cook for a 1/2 penny. My mother used to send Doris to the bakers with our food. There were also some thatched cottages on the Green, and I remember that one caught fire and the fire spread to all of them. It was quite a blaze and us children all went to watch as the firemen tried to put out the fire.

At Christmas Mrs Morrell came over from Goring in her pony and trap. Goods had already been brought to the school and stored there. She would collect them and deliver them personally to homes in the village. Gifts such as blankets, household goods and foodstuffs etc were very well received. She also provided, free, a supply of coal to each family. We were a larger family and I remember we would be given half a ton, tipped on the grass verge outside our cottage. My job was to help to move it to our coal store. Other families would get 5 cwt.

Christmas was an exciting time for the village children. We did not have a Christmas tree but we collected holly to decorate our home. We each had a sock at the end of the bed and our Christmas gift was an orange and a penny.

The village children all played together, sometimes getting into mischief. We went blackberrying, scrumped fruit, climbed trees, went swimming - all the usual things. There was one very sad day when a young lad was out on his tricycle and drowned in the lock. I remember going to his funeral. I played football for the village team, although our field was prone to flooding.

There were 2 more children in our family, Gertrude was born in 1920 and Joan in 1923.

But my mother became very ill and when she died in 1926 from cancer my happy childhood in Culham came to an end. Her grave is to the left of the gate into the churchyard, but the cross on it has broken.

My maternal grandparents offered to take one child to ease the burden on my father. They lived near London because my Grandfather was a Verger at St Paul's Cathedral.

My older sister was needed to look after the younger ones. I always think that I was chosen to be sent away because I ate the most, and wasn't needed to look after the little ones (aged 3, 6, 9 and 12). So my father found the money for a new set of clothes and I was sent away, a devastating experience for a child of 14 who had just lost his mother. I never lived in the village again, but as a young man with a motorbike I came home as often as I could, and I brought my first daughter to be baptised at Culham Church.

1926 - In my new clothes:

Culham through the Looking Glass

Culham through the Looking Glass, a Peep into the Past, by Leonard G R Naylor MA, sometime Vice Principal of Culham College.

Reproduced from the Victoria County History of Oxfordshire volume VII (1962), ed. M.Lobel, by permission of the Executive Editor. The date of the document is unknown.

This account is largely an abridgement, occasionally an expansion, of the author's history of the parish printed in the Victoria County History of Oxfordshire, vo1 VII. The sources used in compiling the history will be found there. That document has now been published in British History Online.

The parish of Culham divides geographically into three distinct sections. Most of it lies between Clifton Hampden and a backwater of the Thames once known as Swift Ditch:Andersey Island, comprising the area between the backwater and Abingdon; and the Otneys, an area on the right bank of the Thames adjoining the west side of Sutton Courtenay.

The origins of the parish system go back to Anglo-Saxon times. We do not know when the parish of Culham first came into existence, but a survey of it was made in 940 in the time of King Edmund. The boundaries of the parish seem to be exactly as now, except for the loss of some eyots in the river to Abingdon in 1894.

Thus the parish has a continuous history of more than 1,000 years. The survey mentions the ford where Abingdon Bridge now stands and refers to 'barrows' (earthworks) at some points along the Parish's eastern boundary; but all trace of the barrows has long since disappeared. In the old days, when Parish boundaries were not always clearly delineated, it was customary to "beat the bounds", i.e. for the vicar and parishioners to march in procession once a year along the boundaries. This was regularly done at Culham during the Middle Ages and led to an amusing incident in 1416. Sir John Drayton of Nuneham, apparently believing that the vicar and his flock were trespassing during the perambulation of that year, is said to have fired at them with a cannon from a fortalice. The frightened Culham men beat a hasty retreat and reported the incident to their Lord, the Abbot of Abingdon, who instituted legal proceedings against Drayton, claiming that the fortalice was on Culham soil. We do not know the result of the action, but there is no sign of any further incidents.

The boundaries of Culham except in the east and the Otneys were formed by the River Thames, which sweeps round three sides of the parish. Yet although a river is usually a natural means of communication with other districts, Culham's communications north and south were not easy. The Thames was certainly navigable during the Middle Ages from London to Henley, and perhaps to Burcot; but the barges moving upstream from Burcot had to face a shallow, rocky bottom at Clifton and a very tricky passage through Sutton to Abingdon. There was, of course, no Clifton or Culham Cut until the 19th Century. At Abingdon the river was again shallow and there were numerous obstructions on the way to Oxford. Hence the wharfage for Abingdon came to be at Culham. We know, for instance, that stone and lead from the dissolved Abbey of Abingdon were brought by road to Culham Wharf to be loaded upon barges for transportation to London. In Tudor times barges became bigger and this made it almost impossible for them to moved between Burcot and Oxford. Hence by two Acts of 1605 and 1624 Parliament set up the Oxford - Burcot Commission to improve the passage of the Thames between these places.

The Commission did much to improve the river between 1624 and the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642. It built the first pound locks on the Thames at Iffley, Sandford and Culham. The Culham Lock was constructed about 1636 in a new cutting at the head of Swift Ditch, which was made the main artery for the barge traffic. The remains of the lock can still be seen as well as the assembly pool for barges that lay near it. There was a flash lock about half way along Swift Ditch, which existed at least as early as 1585. Swift Ditch remained the chief navigation channel until 1790 when it was abandoned in favour of the present route through Abingdon. Water communications through Culham were made much easier in 1809 with the construction of The Culham Cut and Lock. The Cut was made partly along the line of the old Speel Ditch, a straggling channel that left the Thames at the head of the present Cut and turned south to rejoin the river near Sutton Mill. The cost was about £9,000; as usual much more than the original estimate of £5,485.

Communications by road were poor until the early 15th Century. The main Dorchester - Abingdon road runs through the parish from east to west, but before the reign of Henry V the traveller from Dorchester had to ford the river both at Culham and Abingdon. The highway from Dorchester to Abingdon is undoubtedly very old - it is said in an Act of Parliament of 1416 to have existed from "time immemorial". Between 1416 and 1422 a major scheme for improving communications between Abingdon and Culham was undertaken by the Abingdon Guild of the Holy Cross. Abingdon Bridge, the causeway across Andersey, and the old bridge at Culham were built at the Guild's expense. The old bridge is built across the site of the ancient ford known as Culham Hyth; it is of stone and has five perpendicular arches. It lies just to the south of the new bridge erected in 1928 by the Oxfordshire County Council. For centuries it was maintained by Christ's Hospital, the successor to the Guild of the Holy Cross. The highway, however, like all roads before the 18th century, was often in a bad state. Hence the establishment by Act of Parliament in 1736 of a turnpike trust to maintain the roads between Henley and Abingdon; the trust was empowered to levy tolls for the repair of the roads. For instance a coach, chariot, chaise or calash (hooded carriage) drawn by six horses paid a fee of 1/6; if drawn by four hourses 1/-; if drawn by fewer than four horses 6d. A wagon, wain, cart, carriage drawn by four or more horses paid 1;-; if by fewer than four horses 6d. A horse, mule or ass was charged 2d; a drove of oxen 10d. a score; a drove of calves, hogs, sheep or lambs 5d. a score. There were numerous exemptions. Carts carrying materials for the repair of roads; carts carrying manure, hay, straw, timber, ploughs and harrows for the use of the parish; horses and cattle being moved to watering places; soldiers on the march; His Majesty's mails - all these paid nothing. The fees were varied by later Acts of Parliament - altogether there were six between 1736 and 1841. Not until 1875 were tolls completely abandoned. The trust set up toll-houses at Culham Bridge and at the junction of Thame Lane with the main highway. The toll-houses are still standing, a remainder of by-gone days.

The highway is joined near the Wagon and Horses Inn by Thame Lane, which used to continue its journey across Clifton Heath. It was cut in 1941 when a Royal Naval Air Station was built on the east side of the railway line between Didcot and Oxford. A field to the north of Thame Lane bounded by the railway line was probably the site of the Abingdon races, held on Culham Heath from the 1730's to 1811. Jackson's Oxford Journal of 19th September 1767 describes the course in these words: "The Course is most judiciously laid out, both as a piece of fine racing ground, and also for affording diversion for the company, as the horses may be seen quite round from an easy eminence, without moving from the spot." Visitors from Oxford could approach the racecourse by a road, or rather track, from Nuneham.

Culham village was never on the main road. The village High Street is part of a long loop beginning at the Wagon and Horses and ending at Culham Bridge. Before 1813 the straight stretch of road from Culham Bridge to the Village green, cutting through Bury Croft, did not exist; the main highway was linked to the village by a road running close to the west side of Culham House. This road was closed when the straight stretch of road to the Bridge was made. Before 1807 a road from the Wagon and Horses ran to the ferry which took travellers over the Thames to Sutton. The ferry lay just to the west of the present bridge. Built in 1807, it was extended over the Culham Cut in 1908. It was privately owned until 1939 when it was jointly purchased by the Berkshire and Oxfordshire County Councils.

The railway line from Didcot to Oxford runs through the eastern fringe of the parish. It was built in 1843 and 1844 after the objections of local landowners, the University and the city of Oxford had been overcome. The local station was known as "Abingdon Road" and was served by horse-drawn omnibuses from Abingdon which were timed to meet the trains. When Abingdon secured its own station in 1856 "Abingdon Road" was rechristened "Culham".

Culham has played little part in national history and has produced no one of eminence. Yet there is a good deal of interest in its history. Its old English name (Cula's Hamm) suggests a possible 6th Century Anglo-Saxon settlement in the bend of the river, and it was a place of some importance in later Saxon times. For six centuries it was a possession of the Abbey of Abingdon, though the Abbey did not have continuous possession before the middle of the 10th Century; and it was 150 years after that before the Abbey finally secured Andersey. The Mercian King Offa (d.796) is said to have had a hunting lodge on Andersey. The remainder of the parish was apparently in royal hands at this time. The abbey later claimed that King Kenwulf of Mercia (796-821) had granted Culham to it and produced two charters, dated 811 and 821 to prove its case. The charters are certainly spurious, but may nonetheless have a basis of truth. The forgery of documents by monks was a not unusual procedure in the Dark Ages; they probably forged them to ensure their Abbey's possessions had a legal basis. This may well be the case with Culham. Certainly Culham enjoyed a spell of royal favour in the Middle Ages.

King Kenwulf's two sisters retired here to lead a holy life, whilst in 940 King Edmund is said to have granted Culham for life to a royal lady called Aelfhild. After the Conquest both William I and William II stayed at the hunting lodge on Andersey, the Conqueror, we are told, once recuperating there from blood-letting! But the hunting lodge and other buildings on Andersey disappeared when Henry I in 1101 finally returned the island to the Abbey. The memory of them lasted much longer. When the itinerant antiquarian Leland visited Abingdon in the early 16th century he chronicled the onetime existence of a fortress on Andersey.

The manor of Culham remained in the hands of Abingdon Abbey until the dissolution of the Abbey in 1538 when it was seized by the Crown. In 1545 Henry VIII granted it to a London wool merchant, William Bury, in exchange for land in the Isle of Sheppey and £600. William Bury was the second son of Edmund Bury, of Hampton Poyle, Oxfordshire. William Bury (?1504 - 63) must have acquired a substantial fortune as a wool merchant and also attained a position of some importance in the City of London. He was a member of the Common Council and witnessed the will of King Edward VI in favour of Lady Jane Grey. He was, then, clearly a Protestant in religion, though we know nothing of his change of faith. As he survived the reign of Mary he no-doubt dissembled his Protestant beliefs for a time. He was buried in the church of St Swithin, London Stone, in 1563, leaving by his first wife - he was twice married - some seven children.

His eldest son John (1535-72) succeeded him at Culham. He died in 1572 after being thrown from his horse and breaking a thigh, and was buried in Culham Church, the first of many Burys to be interred there. The Bury vault lies beneath the floor of the nave, and there are a number of inscriptions to members of the family still to be seen in the Church. John was succeeded by his infant son Thomas (c1566-1615), who in 1610 refronted the manor house. The date and the initials "T.B." can be seen carved on the new central porch. Thomas married Judith, daughter of the well-known Protestant theologian, lawrence Humphrey, D.D., President of Magdalen College, Oxford, and Dean of Winchester. She survived her husband for more than 40 Years and twice remarried. Her third husband was Sir Edmund Cary (c.1558-1637) Cary was a first cousin once removed to Queen Elizabeth I, his grandmother, Mary Boleyn being sister to Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII, and mother of Queen Elizabeth. Judith was so proud of this marriage that she erected a memorial tablet in the church to herself as well as her husband shortly after his death. She survived him for nearly 20 years, dying in May 1656 at the age of 88. She had two sons by Thomas Bury: Edmund, who was drowned returning from the Netherlands, and William (1594-1632); who succeeded his father.

William left three sons and one daughter, his heir George being only 10 at the time of his father's death. George matriculated at Lincoln College, Oxford, in 1640; and although of military age seems to have avoided active participation in the Civil War. There is nothing to indicate which side he favoured, King or Parliament. Perhaps he succeeded in walking the tightrope of neutrality. When he died in 1662 the direct male line of the Burys ended. His heiress Sarah (1650-80) married in 1666 Sir Cecil Bisshopp, 4th Baronet, of Parham, Sussex. By this marriage the manor of Culham passed to the Bisshopp family, who retained it until 1828; but after Sarah's death in 1680 they spent little, if any, time here. The eighth baronet, also a Sir Cecil, successfully claimed in 1815 the dormant peerage of Zouch de Haryngworth, as the name 'Zouch Farm' reminds us. Lord Zouch died in 1828 without heirs male, and his estates were accordingly divided between his two daughters, the younger, Katherine Arabell, wife of Sir George Brooke-Pechell, Bt., receiving the Oxfordshire lands of Culham and Newington. By 1856 the Brooke-Pechell estates were in debt to the tune of £40,000, and the Culham lands were accordingly sold for £72,750 to James Morrell, of Headington, in whose family they substantially remain.

When Culham belonged to the Abbey of Abingdon it certainly enjoyed a privileged position, its privileges probably deriving from a wider interpretation of King Kenwulf's Charter of 821. The parish claimed to be exempt from taxation, a claim upheld in 1291, but not one likely to be accepted by Her Majesty' Government in 1967! This claim no doubt is the reason for the absence of any mention of Culham in Domesday Book - to the great loss of the historian. The parish too claimed sanctuary rights; abuse of these rights led to them being disallowed in 1486, though a claim to sanctuary at Culham is recorded as late as 1507. With the dissolution of Abingdon Abbey the privileged position of Culham came to an end.

The parish experienced some excitement during the Civil War between King and Parliament in the 17th century. Culham's proximity to Abingdon and Oxford - Charles I's headquarters - meant that the village was bound to be affected by the struggle, for the bridge across Culham Ford was of considerable strategic importance. Abingdon, Dorchester and Wallingford as well as Oxford were at first in Royalist hands; and so naturally was Culham, though we know nothing of the sympathies of the inhabitants. In the spring of 1643 the Royalists had an encampment on Culham Hill; Parliamentary Spies' estimates of the number of troops there varied from 1500 (a reasonable figure) to 20,000! Some trenches were dug and damage to corn fields was reported. The troops, however, were withdrawn to Oxford in June.

But the chief incident of the war so far as Culham was concerned was the skirmish at Culham Bridge in January 1645. The Royalists surrendered Abingdon to the Roundheads in May 1644 in mysterious circumstances, and Culham consequently came under Parliamentarian Control. Culham Bridge was seized and raiding parties were sent out from Abingdon to attack Royalist food convoys moving through Dorchester to Oxford. The inconvenience caused by these harassing attacks was sufficient to induce the Royalists to plan a surprise attack on the bridge. During the early hours of Saturday, 11th January 1645, a Royalist force from Oxford, commanded by Sir Henry Gage, a Roman Catholic, left Oxford via Magdalen Bridge with the aim of seizing and demolishing Culham Bridge. They came to Nuneham-Courtenay, and thence probably by the Nuneham-Culham road to Thame Lane. The morning was misty, the surprise almost complete. The bridge was quickly seized, and one of the two sentries guarding it killed; but the other escaped in the mist along the causeway to warn the Parliamentary commander in Abingdon, Major General Richard Browne, of what had happened. Browne, according to his own account, at once sent troops through the meadows alongside the causeway to outflank the Royalists, who were driven from the bridge into the adjacent hedges and banks.

After some four hours of fighting the Royalists withdrew, carrying with them their mortally wounded leader, Gage. He was buried in Christ Church Cathedral. Other accounts say that Gage conscripted the inhabitants of Culham to demolish the bridge and that some damage was done to it before the Roundheads counterattacked. The Roundheads made the most of their victory for propaganda purposes. One source accuses the Royalists of "plundering Culham most miserably, stripping from divers women of rank all their clothes, took from the Lady Cary, an ancient lady, sick in her bed, her rings from her fingers, watch and whatever they could carry". Whatever the truth of all this may be, the villagers must have had a very unpleasant morning and have greeted the end of fighting with relief. Not until the second World War did Culham again hear the sound of battle.

The villagers who greeted the end of the Civil War with relief were mostly poor and had been so for centuries. The great majority of them obtained a bare living from agriculture, farming strips of land in the great open fields which surrounded the village. Originally there were two vast arable fields, perhaps even as late as 1539; for a survey of that year speaks only of Town and Contard Fields. By the middle of the 17th Century there were three fields ( Ham, Middle and Contard); during the 18th century there was a change to a four field system. The enclosure Award of 1813 mentions four fields: 1. Contard - forming a triangle between the main highway and Thame Lane and ending in the east at Culham Heath, 2. Ham - south of the main highway, from the Clifton boundary to a point perhaps half way between the Wagon and Horses and the boundary, 3. South Middle Field - the remainder of the arable area south of the main highway, 4. North Middle Field - mostly north of the main highway between the Wagon and Horses and Culham Bridge, and also north of Thame Lane for a short distance at its western end.

The exact boundaries of the fields are hard to trace. They comprised altogether some 700 acres. The strips or furlongs in these fields provide us with some fascinating names. Lower Sands, Gogmire, Hornshalt, Hornton, Toot are a few examples. Apart from the arable land there were before enclosure a number of hedged meadows and pastures: these were to be found on Andersey, on both sides of Swift Ditch and in the north of the parish. In addition Culham Heath was a large tract of land in the north east of the parish south of Nuneham Park and reaching in places the main Abingdon-Dorchester Road. After enclosure much of the heath was drained and brought under cultivation. Despite the agricultural changes of the late 18th and 19th centuries much poverty continued amongst the inhabitants, perhaps the worst crisis being in 1800-1 when the parish supported 40 paupers and spent over E 1,000 in relief. But some people were always better off than the peasantry. Indeed the 18th century saw the appearance of large farms; in 1$05 there were five substantial farms and six small ones. Tye, Warren and the Manor Farm were the best known. There were about 40 Houses in the village at this time.

The houses lay mostly north and south of the main village street, i.e. the present High Street, though for most of its length the old street was farther north, i.e. nearer to Culham House, than the present High Street. The alteration to the present line was made between 1810 and 1813 at the time of enclosure when the road across Bury Croft was constructed. The name 'Bury Croft' incidentally has nothing to do with the Bury family; it is found in the survey of 1539 before the Burys came to Culham. Most of the village was rebuilt in 1869 and 1870 and consequently few of the old dwellings survive. Indeed the only old cottage still in existence is the village store, of 17th century origin and refronted in the 18th century. Not even the inns can claim much antiquity. The parish now has three: the Wagon and Horses, the Lion and the Jolly Porter (formerly the Railway Hotel). The Wagon and Horses can be traced back to 1795, though the building is early 19th century; the Lion (formerly the Sow and Pigs) is a fairly modern building, but it too can be traced back to 1795; the Jolly Porter was built about 1846. In the late 18th century there were half a dozen malthouses in the village.

Culham's oldest Building is the Manor House, originally a medieval grange of the Abbots of Abingdon. The house is largely of 15th century date, but in 1610 Thomas Bury rebuilt the north front. Bury's house was much larger than the present one, for an eastern section was demolished during or after the Civil Wars. There is still a room within the house called the Abbot's Chamber which once had heraldic glass depicting the arms of Abbot Coventry, who died in 1512. In the grounds is a dovecote, dated 1685, and bearing the initials of Sir Cecil Bisshopp. It is believed to be one of the three largest in England. When the Bisshopps ceased to bother with Culham, the Manor House began a long period of decline; for many years it was a farmhouse.

The largest house in the village is Culham House, built about 1775 by John Phillips, lay rector of the parish. Phillips was a London builder. His ancestors hailed from Hagbourne and became master carpenters to George I and George II. The Phillips family first appeared in Culham about 1736 and were here until 1935. As lay rectors they were entitled to sit in the chancel of the church and were also legally responsible for the chancel's upkeep. Several memorials to members of the family are in the church. John Phillips erected a handsome redbrick building of five bays, with contemporary staircase, overmantles and doorcasis. The house was enlarged about 25 years later to seven bays. It was once noted for its collection of china.

The old Vicarage was built about 1758, probably by Benjamin Kennicott, vicar of Culham 1753-83. It was enlarged by a later vicar, Robert Walker, in 1849. It has now been sold by the church authorities.

The only large building beyond the confines of the village is Culham College of Education. The building, erected in 1852 was designed by Joseph Clarke, a minor architect of the Victorian era. Clarke designed the College in the neo-Gothic style which was fashionable at the time. It was intended for 100 students, a large number for those days. The original building has been much altered and adapted in the last 20 years, whilst many new buildings, modern in style, have sprung up. The College has now more than 400 students in attendance. A masculine stronghold for more than 100 years, it is now in process of transformation into a co-educational institution. Until 1931 the College had its own practising school, now the craft centre. In the 1960s there was a maximum of 600 students.

There is no sign of any school in the parish before the early 19th century. In 1808 younger children learned to read and write in two small schools, presumably held in cottages; in 1815 a Sunday School was started, its master being paid from the rates. Nevertheless, provision for education was very unsatisfactory until 1850, when the village Church of England School was erected at a cost of £438. Some additions to the premises were made in 1897. Usually a mixed all-age school, it was reorganised in 1924 for infants and girls only, but in 1931 the senior girls were transferred to Dorchester. Temporarily closed in 1948, the school was re-opened in 1951.

Before 1833 education was regarded as the privilege of private individuals and of the Church. In Culham the Church seems to have done little for education before 1815, but in other ways it had played a vital part in the lives of the villagers since Saxon times. It baptised their children, married them and buried them; the vicar was their guide, philosopher and friend. He counselled those in need of advice, he visited the sick, he presided over meetings of the vestry, the body that formed the local government of the parish. The members of the vestry were the better-off parishioners, who in turn served as churchwardens, overseers of the poor and highway surveyors. The parish church was usually their meeting place. In most English parishes the church can be traced back to the Middle Ages and its story is an epitome of the history of England.

The church of St Paul at Culham has unhappily little that is old in its structure. As an historical 'document' it cannot compare with its neighbour at Sutton Courtenay. The oldest part is the tower and even that dates only to 1714 though there was certainly an earlier tower. The present church was built in Victorian times, the Nave in 1852 and the Chancel in 1872, The Nave which is in the Early English style, was designed by Joseph Clarke, the architect of Culham College; the Chancel by R J Spiers. The cost of rebuilding the Nave - the medieval Nave was beyond major repair by 1852 - was borne partly by a parish rate and partly by donations; The Chancel was rebuilt at the expense of the lay rector, John Shawe Phillips. The church was refitted after rebuilding. Neither the building itself nor the fittings are attractive. A communion table dated 1638 and an ancient parish chest have survived the Victorian onslaught. The stone font was given about 1845 by J S Phillips; before that time a baptismal font of gilded base metal resting on a mahogany stand was used. There are memorials in the church to some members of the Bury family, to Sir Edmund and Judith Cary, to members of the yeoman family of Welch, and to members of the Phillips family. Other memorials of the Burys have been lost.

The damage done to churches by the Victorian "restorers" may well have exceeded that done by the extreme Protestants of the days of Edward VI and 0liver Cromwell. Certainly little attempt seems to have been made at Culham to preserve the relics of the past. We do, however, know a good deal about the old church of St Paul thanks to a detailed description given in Parker's Guide to Antiquities near Oxford published in 1846 and to an early 19th century drawing of the south side preserved in the Bodleian Library.

The medieval church stood on the site from the late 12th or early 13th century to the middle of the 19th century; there may well have been an earlier building, perhaps going back to the time of King Kenwulf. But if there was, we know nothing about it. The medieval church was about the same length as the present building, but had a narrower nave. It had a south aisle, separated from the nave by five small pointed Early English arches, and a north and south transept. The east end of the chancel was square, not apsidal as it is now. There was a Decorated window of two lights in the wall of the south aisle. The south transept had a similar window on its east side and another of three lights at the end; above this window was a sundial. The porch was much closer to the south transept than the present porch, and the line of the roof was lower.The north side of the building seems to have been poorly lit. It had only a single lancet window in the wall, though there was a range of four clerestory windows above. In the north transept, however, in a little chapel, was the chief glory of the old church, the north window, which was filled with heraldic glass, the jambs containing chains of heraldic shields with the arms of different families, principally Cary and Humphrey; on each side was a two-light lancet window. The glass was inserted in 1638 and forms part of the Cary memorial. When the church was rebuilt much ofthe glass was placed in a window in the north aisle. Alas! some of the glass was lost and a good deal of the remainder barbarously mishandled. This is not the only heraldic loss. A high window on the north side of the nave once contained the arms of an Abbot of Abingdon. It is not known when this disappeared, but it was in place in 1717. Will we never learn the lessonof the need to guard our historical relics? Within the last 30 years there have been further losses: the first parish register beginning in 1648 - though fortunately a transcript was made of this in the 1930's. Of the original church plate, only two pieces remain; the oldest, an Elizabethan silver chalice (dated 1575 and a silver plate given by the Revd Benjamin Kennicott in 1761. A silver flagon given by the Revd Thomas Woods in 1752 and another silver patten, given by the Revd Robert Wintle in 1829 have been lost at some time within the last 40 years. In the last three years several additions have been made, notably a modern silver chalice with walnut stem and a silver-gilt chalice and patten, the gift from a neighbouring parish. Three of the bells in the tower are old, one dating back to 1597, the other two being 18th century. There is a sanctus bell dated 1774, which is hung. for chiming; it was cast by Edne Willis, of Aldbourne, Wiltshire, and is the only bell known to be by him.

For many centuries Culham was an ecclesiastical 'peculiar' i.e. it was free from the control of the bishop. In the Middle Ages the church was completely dominated by the Abbot of Abingdon, who did not need to present his nominee to the living to the bishop. Hence the names of only three pre-Reformation priests are known. At the Reformation possession of the living passed to the Crown, and thence in 1589 to the Bishop of Oxford. As the value of the living was very small it attracted few distinguished names; and if such men held the living they were usually absentees. Thus Thomas Woods, vicar 1739 - 1753, was as headmaster of Abingdon School, non-resident; and his successor, Benjamin Kennicott (1753 - 1783), lived in Oxford. Kennicott was a distinguished Hebrew scholar and librarian of the Radcliffe Camera in Oxford. That he occasionally appeared in Culham is shown by his signature in the Churchwardens' Accounts from time to time. A 20th Century vicar (1911 - 1917) was the Oxfordshire antiquary, W J 0ldfield. He put the parish records in order and indexed the registers.

The parishioners seem to have accepted all the changes produced by the Reformation without protest and Roman Catholicism rapidly declined. Only occasional references to Roman Catholics are to be found in the 17th and 18th centuries. Nor is there anything to suggest that Culham was affected by Protestant Dissent. There was never more than a handful of Dissenters in the parish before the 20th Century and they probably worshipped in Abingdon. No meeting place for Dissenters was ever established.

It is time to end this brief survey. Culham, in the course of its known history of more than 1,000 years, has seen many changes in the evolution of England and many changes within its own boundaries. Yet basically it remains a unity despite the economic and social pressures of the 20th century. Whether this unity can remain is a problem which only the future can solve. Perhaps the next historian of Culham will be able to answer the riddle.

Culham Manor and Church

By Rev F Denman, Vicar 1976-81. Found in the church safe.

For centuries the life of Church and Manor have intertwined. The core of the ancient Manor House has largely survived but alas, of the ancient church nothing remains - only that same 'peace' which our forbears treasured. The story begins in the seventh century, when already there was a handful of men leading a some sort of 'holy life' in that part of Culham known as Andersey Island. St Birines had been preaching to the West Saxons in and around Dorchester since 634 A.D. The ancients had buried their dead on Andersey (St Andrews Isle). Although burial mounds have disappeared there are burial mounds within the grounds of Culham Manor. On the Eastern boundary between the village pond and the vegetable garden there remains a fine Long Barrow and early Ordnance Survey plans indicate a tumulus immediately to the East of the front garden upon which there grows a Horse Chestnut tree. While the monks were on Andersey, Royalty also discovered the charm of Culham and in pursuit of sport King Offa, in 790 established his ascendancy over the West Saxons at Culham. He liked it so much that he built a royal residence very close to what is today Rye Farm. His son, Egbert, died at this hunting lodge. The monks, who at that time were building Abingdon Abbey, were very much inconvenienced by the sport of Kings, according to translations.

Following the death of Egbert, King Kenwulf (or Coenwulf) discovered Culham and soon this King of the Merciars acquired Culham for himself. King Kenwulf had two sisters called Kerieswyth and Burgevilde and according to ancient records they were good looking Ladies with elegant manners and entirely devoted to God. When the King spoke to his sisters of marriage they told the King that from their girlhood they had desired, with all their mind and strength, to serve and please God only. The King was very happy to comply with their wishes and this request was granted. They also asked him for a portion of land where they might remain in God's service. So in 801 King Kenwulf granted them the Land of Culham: A suitable dwelling place and chapel were built and the two sisters began to lead a life of prayer, love and devotion to God. It is from this and on this hallowed ground that Culham Manor and Parish Church now stand. The two holy sisters asked that when they died they should be buried in Abingdon Abbey and the property at Culham to be given to the Monastery.

The holy and exemplary life of the two sisters became widely known, King Kenwulf, delighted by his sisters way of life and faith granted further favours to Culham which had now become known as a 'holy place'. Culham Church was given the rights of 'Sanctuary' - a haven of protection for the innocent and unjustly treated. The Sanctuary was inviolable but alas, later on in history it became a protection to hosts of thieves, robbers and murderers. King Kenwulf also stated that Culham inhabitants were free from every secular demand, even from obedience to the command of the King and his ministers and even taxes. Culham and its people were subject only to the Abbot of Abingdon. There is a tradition that Abbot Rethan himself journeyed to Rome to receive special favours granted to Culham from the Pope and it is a fact that Pope Leo III confirmed these privileges on Culham in 802.

In the year 940 a sister of King Aethelstan, King of the West Saxons and Grandson of Alfred the Great, no doubt inspired by the reputation of Culham, came to live here a similar life to her royal predecessors, Her name was Aelfhild and she caused a new and fine chapel to be built and dedicated to St Vincent. When Aelfhild died she was buried in this chapel but, sad to relate; nothing remains of her tomb.

The next we hear of Culham is from Pope Gregory IX (1227 - 41). He confirmed that Culham Manor and its chapel belonged to the Abbey of Abingdon. It is probably at this time that, because of its reputation as a retreat and 'holy place', the house and church became a religious settlement in its own right - what was known as a 'Grange'. This was like a monastery with its daily rule of life and yet not independent of the Great Abingdon Abbey. Barns and Outbuildings were built for the Prior and half a dozen or so Monks who were under the Benedictine rule of manual work on the land combined with regular prayer life. In 1289 it is recorded that the Prior of Culham, Nicolas by name, was elected Abbot of Abingdon, a great honour. Later it seems a shadow appeared on the holy life at Culham with the abuse of its rights of Sanctuary, In 1394 the crown petitioned against the abuse of sanctuary and in 1442 Pope Eugenius IV issued a mandate to the Bishop of Lincoln and others to enquire into such abuses.

In 1456 events took a dramatic turn. The army of Richard III had been routed at the Battle of Bosworth Field the previous year and the new King Ilenry VII was anxious to get rid of any traitors. A rebellion lead by Lord Lovell against the King sprang up which was supported by Sir Humphrey Stafford and his brother Thomas. The rebellion failed and Sir Humphrey and his brother fled to Culham. The King decreed that Culham was not sufficient defence for traitors and the unfortunate brothers were dragged from Culham Church and conveyed to London. Sir Humphrey was executed at Tyburn but Thomas was pardoned on the grounds that he was influenced by his brother.

The manor remained in the hands of Abingdon Abbey until the dissolution of the Abbey in 1538 when it was seized by the Crown. In 1545 Henry VIII granted the manor and its lands to a London Wool Merchant, William Bury, in exchange for land in the Isle of Sheppey and £600. William Bury was the second son of Edmund Bury, of Hampton Poyle. William Bury 1504 - 63 must have acquired a substantial fortune as a wool merchant and also attained a position of some importance in the City of London. He was a member of the Common Council and witnessed the will of King Edward VI in favour of Lady Jane Grey. William Bury was a protestant by faith although having survived the reign of Mary he no doubt dissembled his beliefs for a time. Twice married, he left seven children and his eldest son John succeeded him at Culham. John Bury (1535-72) died after being thrown from his horse and breaking a thigh and was buried at Culham Church, rededicated to St Paul at the beginning of William's life at Culham. The Bury vault lies beneath the nave.

John was succeeded by his infant son, Thomas (1566 - 1615) who in 1610 refronted the manor in Jacobean style and the initials "T.B." and the date 1610 can be seen carved on the new central porch on the North Front. His work did not entirely erradicate the original medieval frontage of the house and the window and door lintels can still be seen carved out of the timber beam set some five feet inside the porch and in the truss of the North West Bedroom. Thomas Bury was married to Judith Humphrey who inherited the house after his death. She twice remarried, surviving Thomas by more than fourty years: Her second husband was Sir George Rivers and her third husband was Sir Edmund Cary who was a first cousin once removed to Queen Elizabeth I. His grandmother, Mary Boleyn, being sister to Anne Boleyn, second wife to Henry VIII and mother to Queen Elizabeth, On the death of Sir Edmund Cary, Lady Cary erected a Tablet in Culham Church in 1638 as a memorial to herself as well as her late husband, and this Tablet still remains.

The parish experienced some excitement during the Civil War between King and Parliament in the 17th century. Culham's proximity to Abingdon and Oxford - Charles I's headquarters - meant that the village was bound to be affected by the struggle, for the bridge across Culham ford was of considerable strategic importance. Abingdon, Dorchester and Wallingford as well as Oxford were at first in Royalist hands; and so naturally was Culham though we know nothing of the sympathies of the inhabitants. In the spring of 1643 the Royalties had an encampment on Culham Hill; Parliamentary spies' estimates of the number of troops there varied from 1500 (a reasonable figure) to 20,000! Some trenches were dug and damage to corn fields was reported. The troops, however, were withdrawn to Oxford in June. But the chief incident of the war so far as Culham was concerned was the skirmish at Culham Bridge in January 1645. The Royalists surrendered Abingdon to the Roundheads in May 1644 in mysterious circumstances, and Culham consequently came under Parliamentarian control. Culham Bridge was seized and raiding parties were sent out from Abingdon to attack Royalist food convoys moving through Dorchester to Oxford. The inconvenience caused by these harassing attacks was sufficient to induce the Royalists to plan a surprise attack on the bridge. During the early hours of Saturday, 11th January 1645, a Royalist force from Oxford, commanded by Sir Henry Gage, a Roman Catholic, left Oxford via Magdalen Bridge with the aim of seizing and demolishing Culham Bridge. They came to Nuneham Courtenay, and thence probably by the Nuneham-Culham road to Thame Lane. The morning was misty, the surprise almost complete. The bridge was quickly seized, and one of the two sentries guarding it killed; but the other escaped in the mist along the causeway to warn the Parliamentary commander in Abingdon, Major General Richard Browne, of what had happened, Browne, according to his own account, at once sent troops through the meadows alongside the causeway to outflank the Royalists, who were driven from the bridge into the adjacent hedges and banks. After some four hours of fighting the Royalists withdrew, carrying with them their mortally wounded leader, Gage. He was buried in Christ Church Cathedral, Other accounts say that Gage conscripted the inhabitants of Culham to demolish the bridge and that some damage was done to it before the Roundheads counter-attacked. The Roundheads made the most of their victory for propaganda purposes, One source accuses the Royalists of "plundering Culham most miserably, stripping from divers women of rank all their clothes, took from the Lady Cary, an ancient lady, sick in her bed, her rings from her fingers, watch and whatever they could carry".

After the death of Lady Cary in 1656 the manor passed to her grandson George Bury who is also reputed to have died from a fall from his horse and it was about this time that a large portion of the E shaped manor was demolished leaving only the L shaped North Western half of the house. Parts remained of the Eastern demolished section- The ground floor cottage North facing window was part of the East Wing although the cottage has been built upon the site. It is also believed, that some of the walls of the walled gardens to the South East of the house are the remains of the stone ground floor section of the half timbered missing wing.

George's daughter and sole heiress, Sarah, married Sir Cecil Bisshopp 4th Bart of Parham, Sussex in 1666. Sarah died in 1679, but Sir Cecil remarried and in 1685 he built the stone dovecot containing upwards of 3000 nesting boxes and which is alleged to be the second largest dovecot in the Country. Sir Cecil Bisshopp died in 1705 and the 8th baronet, another Cecil, in 1815 made a successful claim to the dormant barony of Zouch de Haryngworth. Lord Zouch died in 1828 and the property was divided between his two daughters. However, since 1749 the Manor had become a farm house occupied by the Welch and Mundy families many of whom are buried in the churchyard. By 1856 the estates were in heavy debt and the Manor and lands were sold to James Morrell of Headington in whose family's hands the manor remained until purchased by Mr and Mrs Murphy in 1974.

During the passage of time the manor became seriously dilapidated and encumbered with Victorian additions. In 1933 Sir Esmond Ovey acquired the manor on a long lease from the Morrells and for some fifteen years he renovated and restored the building to its present style, great care being taken to remove the Victorian work and replace the timber members determined by the monks remaining on the old wall plates. In this manner he replaced wood framed casement windows and beams although many are original: The garden on the North side with its rose garden and billowy ewes echoes the early 17th century flavour of Thomas Bury's Jacobean facade. To one side stands an early 17th century sundial mounted on a column that appears to be considerably older. The cobbled path, similar to one at Minster Lovell, leading from Bury's porch to the church was uncovered intact by Sir Esmond Ovey although the existance of such had been rumoured in the village for many years.

Viscount Samuel's Memoirs

Cresset Press 1945, from the chapter titled Oxford: 1889-93. Thanks to Mrs Charlotte Franklin for this extract describing social deprivation in Culham and the surrounding area.

Inquiries afterwards in many other villages in the district showed the conditions everywhere to be substantially the same. Although the environment was of course incomparably better, the extreme poverty which I had found in the squalid slums of Whitechapel was to be seen again in the outwardly charming villages of Oxfordshire. Even the sweated home industries were not absent. In the village of Culham, I had visited a labourer and found that the wife was employed in trouser-making: she worked ten hours a day lining and button-holing; her weekly earnings were from 4s. to 5s. or about a penny an hour. The husband worked similar hours for a weekly wage of 9s. The rent of their cottage was 1s.9d.

Other Notes

The Manor House

The Manor at Culham remained in the hands of Abingdon Abbey as a rest house until the dissolution of the Abbey in 1538 when it was seized by the Crown. In 1545 it was granted by Henry VIII to William Bury, a London wool merchant. The house is largely of fifteenth century origin but in I610 Thomas Bury rebuilt the north front. Bury's house was much larger than the present one, for an eastern section was demolished during the Civil War. The Manor House was in possession of the Bisshopp family from 1666 until 1856 but their interest in it ceased in 1749 and the Manor began a long period of decline; for many years it was a farm house. However, the house was restored splendidly by Sir Esmond Over from its sadly dilapidated state of 1933.

St Paul's Church

St Paul's Church, rebuilt in Victorian times, replaced one of late twelfth century or early thirteenth century origin; the tower is its oldest part, dating back to 1710. The Mediaeval Church was about the same length as the present building but had a narrower nave, In 1852 the mediaeval nave was beyond repair and was rebuilt; the cost was borne partly by a parish rate and partly by donations. The chancel was rebuilt at the expense of the lay rector, John Shawe Phillips.

The Former Post Office and Village Stores

The former Post Office and Village Stores is the oldest cottage still in existence. Most of the village was rebuilt in 1869 and 1870. It is of seventeenth century origin and was refronted in the eighteenth century.

Old Culham Bridge

The old Bridge is of stone and has five perpendicular arches. It was built across the site of the ancient ford known as Culham Hythe between 1416 and 1422 by Abingdon's Guild of the Holy Cross, at their expense. For centuries it was maintained by Christ's Hospital, the successor of the Guild. Culham Bridge was of considerable strategic importance and during the Civil War a skirmish occurred on it early on January IIth, 1645. The Royalists had surrendered Abingdon to the Roundheads in May 1644 in mysterious circumstances and Culham consequently came under Parliamentarian control. Culham Bridge was seized and raiding parties were sent out from Abingdon to attack Royalist food convoys moving through Dorchester to Oxford. These harassing attacks finally drove the Royalists to plan a surprise attack and to capture and destroy the bridge. A force commanded by Sir Henry Gage but with Prince Rupert in attendance left Oxford, and surprised the sentries on the bridge. One escaped, however, and gave the alarm in Abingdon: four hours of battle about the bridge, and the Royalists had to withdraw, taking with them the mortally wounded Gage. We learn that the Royalists compelled local folk to assist in breaking up the bridge, which task was not successful. The raiders were also alleged to have "plundered Culham most miserably,stripping from diverse women of rank all their clothes; took from Lady Cary, an ancient Lady in her bed, her rings from her fingers, watch, and whatever they could carry."

The Former Culham College

Founded by Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, Culham College was erected in 1852, designed by Joseph Clarke in the neo-gothic style which was fashionable at the time. The tower block was opened in 1973 when Teacher Training Colleges were being expanded. Now the European School.